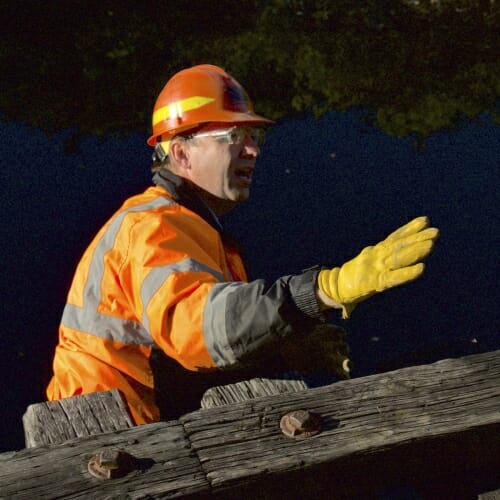

As 20 adult students, clad in dazzling safety vests, clambered over, under and across an old railroad bridge near Oregon, Wisconsin, two experienced railroad bridge inspectors brought the steel structure to life, with an inch-by-inch inspection of its ability to carry heavy freight cars safely.

Unlike highway bridges, railroad bridges must be inspected every year. Problems can be hidden by soil, structure or inadequate inspecting tactics. Many surface slowly, taking decades to reach a threatening point.

Starting from the top, and mixing eyeballs with iron-age inspection tools, the instructors proffered decades of experience to their successors.

The outdoor classroom included five students from Wisconsin and 15 others from Alaska, California, Florida and the east coast. Only a few places teach railroad bridge inspection, notes course director Dave Peterson of Engineering Professional Development at UW–Madison.

When they depart Madison, these professionals will be in a better position to ensure safety on rails that carry passengers, freight and flammable or toxic chemicals. Wisconsin alone has 3,387 miles of railroad track, and approximately 2,000 bridges. Nationally, 1,250 derailments happened in 2017, but almost none are due to bridges, Peterson says.

The course is part of the broad and deep offerings from EPD, which lists more than 200 courses covering everything from refrigeration and landfill design to lean manufacturing and leadership, and serves about 7,000 students per year.

EPD, now a branch of the UW–Madison College of Engineering, began 60 years ago with a focus on technical skills necessary to keep professionals, including many who graduated decades before, abreast of the latest technology.

The first bridge on the afternoon dance card is a steel structure, built by the Chicago and North Western in the village of Oregon in the early 20th century. The bridge, now out of service, is owned by the Wisconsin and Southern Railroad.

There’s a lot to see and evaluate, even with the “simple” but critical element — the ties:

- Are the ties spaced too far apart?

- Are the plates holding the track to the ties shifting under load?

- Some ties have started to split. How many? How much?

- Are the spikes tight, loose or missing?

To check the substructure, instructor Pete Schierloh, a project engineer with SW Bridge Engineers in DeForest, starts with the concrete foundation. One section is obviously a replacement, but the older section, nearby, shows surface degradation. To determine if the soft spot matters, Schierloh whacks it with a rock hammer and listens. Only a few areas return the deep “thunk” that reveals rotten concrete.

Looking up, Schierloh looks at the main beams’ bearing points, and the “how deep?” question resurfaces in the form of rust. As it seems superficial, a repair order is not indicated.

Everything needs to be seen, noticed, recorded. This bridge was built to serve two tracks, until a giant cutting torch severed one half in the distant past. That explains why one bridge beam is so much beefier than the other, since it needed to support a rail on each track.

Evaluating the stone arch bridge at Bram Street on the south side of Madison, Halpin is mostly upbeat, though he does object to an overgrowth of weedy trees, noting that the roots may shift the large stones. Beyond a few dislodged stones, however, the masonry is mostly solid.

At a wooden span crossing Wingra Creek, Schierloh strikes the ties with a three-foot steel rod, noting that occasional “thunk.”

As technology grows and the economy becomes more dependent on it, the need for high-quality courses like this will grow. An aging workforce is a key motivator for the dozen-or-so railroad courses taught annually at EPD, says Peterson. “We are training the next generation of railroaders. There’s a huge gap between people retiring, and the younger professionals in the business, because there was a 20-year period when there was essentially no hiring of technical people in the railroad business.”

David Tenenbaum |University Communications